According to the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), using a three-part framework can be useful to communicate effectively:1

• Goal

• Audience

• Message

Goals can be framed by timeline – short, medium and long term – or in terms of the desired audience response:

• Rational (think)

• Emotional (feel)

• Behavioural (do)

A behavioural goal in a healthcare context might be to change the way doctors manage a particular disease (do), which will require them to think that the new method is better than the one that they have employed to date (rational) and feel confident in how to utilise it (emotional).

In the AAAS model the goal is closely linked to the choice of target audience. Take an issue such as legalising the medical use of cannabis; the communication goals will change depending on whether the activity aims to change the attitudes and behaviour of legislators, prescribers, users, or all three. It has been said that “not knowing your audience is like throwing darts at a dartboard with the lights off”.2

Marketers sometimes think of their target audiences’ minds as blank whiteboards on which messages can easily be written. The truth is the opposite: the whiteboard is already filled with opinions, attitudes, values and feelings that shape current and future behaviour. Finding space for new ideas on these mental whiteboards is difficult, especially when you are seeking to challenge deep-seated opinions, prejudices and possibly irrational behaviours. People are complicated and it is important to understand a wide range of factors before attempting to communicate with them. It is only after gaining this insight that messaging should be considered.3

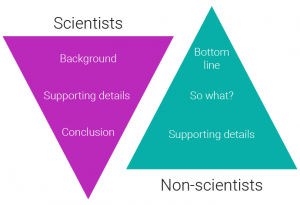

Scientists wanting to communicate successfully with non-scientists will need to turn their usual approach on its head.4

Those with a scientific or empirical mindset, which invariably means most people working in pharma, typically want all the background and supporting details in the communication before being presented with the results and conclusion. This is why most medical papers follow this evidence, analysis and conclusion model. Non-scientists on the other hand want the communicator to get to the point as quickly as possible. They are less interested in engaging with the background material and a slow and steady path to the conclusion. They need to be given a reason to care – typically one that answers the question ‘What’s in it for me?’ The requirement is therefore to be clear and concise, learning from the art of the elevator pitch.2

Picking up on this, the AAAS suggest that communicators should start by asking what three things they want their audience to remember and then ensure that their messages conform with the three Ms:2

• Meaningful

• Memorable

• Miniature

Making the science meaningful and memorable is a big part of bringing science to life and it will only happen if the messages stimulate the imagination of the audience and embrace their emotions. This requires creativity, which can be defined as the ‘relevant unexpected’. The message (verbal and/or visual) must be relevant and therefore aligned with the communication goals; at the same time it needs to be unexpected, delivering surprise by stepping outside of the familiar.

The role of storytelling

To persuade people to act, you have to make them care. Simply presenting facts, data and evidence to non-scientists is more likely to bore them than involve them. However, there is a way to entice your audience to engage with the facts and that is to tell them a story. Stories have been described as facts wrapped in emotion.5 It is claimed that they stimulate more areas of the brain than pure logic by evoking powerful images, leading to emotional responses, which in turn are more likely to be persuasive. Stories help people relate to what is being said, to empathise and to embrace information.6

Stories are therefore a powerful tool in helping bring science to life and yet in essence they follow a simple logical flow, connecting some sort of conflict to a resolution. In a science story the beginning might be dramatisation of a problem; the core could then be an engaging account of what needed to be done to help solve the problem or overcome the obstacles to solving it; the ending could dramatise the outcome, stressing the benefits and positive effects.7

In healthcare stories can be used in numerous ways, helping to connect the results of clinical trials to clinical practice, describing the effects of a new medicine on the treatment of a disease, and highlighting the value of earlier diagnosis. Whatever the theme emotional resonance flows from personalising the consequences. If the audience comprises HCPs this is often achieved by indicating how the problem and its outcome affect them and their patients.

It has also been said that the best bridge between a presenter and an audience is a story and this is especially true when communicating with patients. Telling the right story leads to better awareness, understanding and compliance, potentially resulting in better outcomes.8

Equally patients can be the storytellers. There is a specialised branch of storytelling called narrative medicine that aims “to recognize, absorb, interpret, and be moved by stories of illness”. It is designed to act as a counterbalance to the overuse of dry technological results within a healthcare system and promotes the use of narratives in clinical practice, research and education.9 For example, in a consultation an HCP might deploy storytelling by asking the patient how they feel about their condition, what they think is going on or how their life has changed.10 It is claimed that competence in narrative medicine increases empathy and understanding in diagnostic encounters and therapeutic processes involving HCPs, patients and their families. It can also be used to improve interdisciplinary collaboration by helping HCPs to understand illness narratives from different perspectives.9

Conclusion

It is one thing to believe that it is important to bring science to life; it is quite another to do it successfully. In this regard it is true that inspiration and creativity are helpful. Even so, following a simple set of proven rules or guidelines can save a lot of time and improve the chances of achieving the desired outcome. This includes recognising that humans are storytelling animals. The ability to tell the right story is an indispensable skill if you want to be successful in bringing science to life. It is vital that this skill is acquired and developed by scientists and their advisers who play such an important role in bringing about happy endings.

- American Association for the Advancement of Science. Communication fundamentals. Available at https://www.aaas.org/resources/communication-toolkit/communication-fundamentals. Accessed May 2021.

- Shepherd M. 9 tips for communicating science to people who are not scientists. Forbes. 2016. Available at https://www.forbes.com/sites/marshallshepherd/2016/11/22/9-tips-for-communicating-science-to-people-who-are-not-scientists/. Accessed May 2021.

- Besley JC, Dudo A. What it means to ‘know your audience’ when communicating about science. The Conversation. 2019. Available at https://theconversation.com/what-it-means-to-know-your-audience-when-communicating-about-science-111147. Accessed May 2021.

- American Association for the Advancement of Science. AAAS communication toolkit. Available at https://www.aaas.org/resources/communication-toolkit. Accessed May 2021.

- Olson R. Don’t be such a scientist: talking substance in an age of style. Washington, DC: Island Press; 2009.

- Joubert M, et al. Storytelling: the soul of science communication. JCOM: Journal of Science Communication. 2019;18(5): Editorial. Available at https://jcom.sissa.it/archive/18/05/JCOM_1805_2019_E. Accessed May 2021.

- Ward A. The art of storytelling in clinical data communication – what can we learn from Batman and the Joker? Pharmaphorum. 2018. Available at https://pharmaphorum.com/r-d/views-analysis-r-d/art-storytelling-clinical-data-communication/. Accessed May 2021.

- Gaughran KR. Healthcare storytelling: the best marketing magic and how to do it. Healthcare Success. 2018. Available at https://healthcaresuccess.com/blog/healthcare-marketing/healthcare-storytelling-marketing-magic.html. Accessed May 2021.

- Liao HC, Wang YH. Storytelling in medical education: narrative medicine as a resource for interdisciplinary collaboration. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(4):1135. Available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7068522/. Accessed May 2021.

- Charon R. Narrative medicine: honouring the stories of illness. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006.